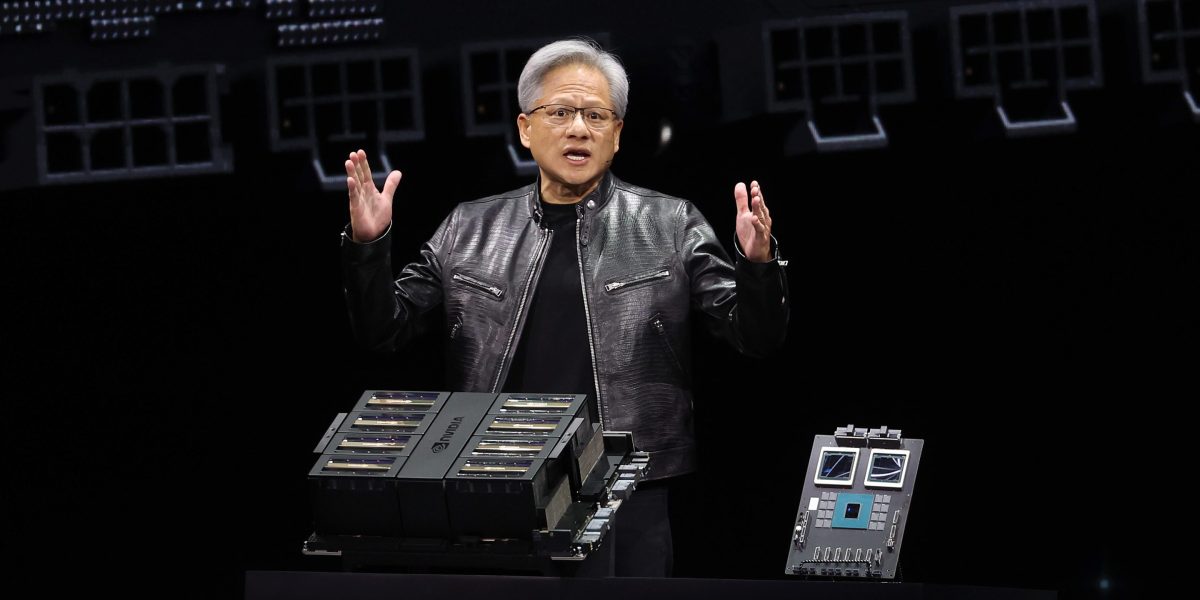

Nvidia’s skyrocketing sales of chips that power AI models like OpenAI’s GPT-4 is among the biggest tech stories of 2024. The rapid growth has fueled a 200% gain in the company’s stock over the past 12 months, leading to membership in the exclusive club of businesses with stock market values exceeding $2 trillion (briefly, its value even topped $3 trillion).

The question many people are asking now is who can beat Nvidia, which lately controls 80% of the AI chip market. But several analysts recently told Fortune that’s the wrong question because, as one of them, Daniel Newman, CEO of the Futurum Group, put it, there is “no natural predator to Nvidia in the wild right now.”

Here’s why: Nvidia’s graphics processing units (GPUs), originally created in 1999 for ultrafast 3D graphics in PC video games, turned out to be perfect for training massive generative AI models, which are growing larger and larger, from companies like OpenAI, Google, Meta, Anthropic, and Cohere. Today, that training requires access to vast numbers of AI chips. For years now, Nvidia’s GPUs have been considered the most powerful and are the most sought-after.

They certainly don’t come cheap: Training the top generative AI models requires tens of thousands of the highest-end GPUs, each of which costs $30,000 to $40,000. Elon Musk, for example, said recently that the Grok 3 model from his company xAI will need to train on 100,000 of Nvidia’s top GPUs to become “something special,” and which would translate into more than $3 billion in chip revenue for Nvidia.

Nvidia’s success isn’t a product of the chips alone—but also the software that makes them accessible and usable. Nvidia’s software ecosystem has become the go-to for a massive cohort of AI-focused developers, who have little incentive to switch. At last week’s annual shareholder meeting, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang called the company’s software platform, dubbed CUDA, for Compute Unified Device Architecture, a “virtuous circle.” With more users, Nvidia can afford to invest more on upgrades to that ecosystem, thereby attracting even more users.

By contrast, Nvidia’s semiconductor competitor AMD, which controls about 12% of the global GPU market, does have competitive GPUs and is improving its software, said Newman. But while it can provide an alternative for companies that don’t want to be locked into Nvidia, it doesn’t have the existing user base of developers building on it who consider CUDA to be easy to use.

In addition, while each of the large cloud service providers like Amazon’s AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud produce their own proprietary chips, they are not looking to displace Nvidia. Rather, they want a variety of AI chips to choose from in order to optimize their own data center infrastructure, keep prices down, and sell their cloud services to the widest potential customer base.

“Nvidia has the early momentum, and when you establish a market that is growing rapidly, it’s hard for others to catch up,” explained analyst Jack Gold, of J. Gold Associates, who said that Nvidia has done a good job of creating a unique ecosystem that others don’t have.

Matt Bryson, senior vice president of equity research at Wedbush, added that it would be particularly hard to displace Nvidia’s chips for training large-scale AI models, which, he explained, is where most of today’s spending on computing power is going. “I don’t see this dynamic shifting for some time to come,” he said.

However, an increasing number of AI chip startups, including Cerebras, SambaNova, Groq, and the latest, Etched, see an opening to pick off small parts of Nvidia’s AI chip business. They’re focusing on the specialized needs of AI companies, particularly when it comes to what’s known as “inference,” or running data through already-trained AI models to get the models to spit out information (every answer from ChatGPT, for example, requires inference).

Just last week, for example, Etched raised $120 million to develop a specialized chip designed specifically to run transformer models, a type of AI model architecture used by OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Anthropic’s Claude. Meanwhile, Groq, which focuses on running models at lightning speed, is reportedly raising new funds at a $2.5 billion valuation, while Cerebras has reportedly filed confidentially for an initial public offering just a few months after unveiling its latest chip, which it claims can train an AI model that is 10 times the size of GPT-4 or Gemini.

All of these startups will likely focus on a small market at the outset, such as providing more efficient, faster, or cheaper chips for certain tasks. They may also focus more on specialized chips for specific industries or AI-powered devices like PCs and smartphones. “The best strategy is to carve out a niche and not try to conquer the world, which is what most of them are trying to do,” said Jim McGregor, principal analyst at Tirias Research.

So perhaps a more pertinent question might be: How much market share can these startups, along with cloud providers and semiconductor giants like AMD and Intel, seize?

That remains to be seen, particularly since the chip market for running AI models, or inference, is still very new. But at Nvidia’s annual shareholder meeting last week, Huang made clear to investors that as rivals push to cut into Nvidia’s market share, the company plans to innovate and continue to be the gold standard in AI training chips.

When Nvidia rolls out its Blackwell system later this year, which will surpass the power of its current H100 chips, it will only cement its lead, he claimed. “The Blackwell architecture platform will likely be the most successful product in our history,” Huang said.

But over the long term, analysts see plenty of areas for rivals to thrive, especially when it comes to their use of electricity, which is a huge cost for companies training and running AI models. “I think that the question of power is one that could create room for competitive alternatives,” said Bryson. “GPU data centers are becoming more and more power hungry as models become bigger, and a solution that reduces power requirements considerably could see substantial traction.”

Nvidia must also watch out for antitrust troubles. Reuters reported on Monday that Nvidia will be charged by the French antitrust regulator for “allegedly anticompetitive practices,” which would make it the first regulatory agency to do so. In the U.S., the Department of Justice is currently leading an investigation into Nvidia. Any antitrust cases could potentially slow Nvidia down while leaving room for smaller rivals to close the gap.

Nvidia’s competitors could certainly use any advantage they can get—since for now, at least, Nvidia appears to be sitting pretty.

“You could certainly make the argument that Nvidia is setting itself up to be almost invaluable, unless they really self-inflict a wound that causes this market to shift,” said Newman. But he argued that the “huge” market for specialty chips should definitely make space for many other players.

“If AI is as big of a trend as we all believe it is, you’re going to have this really healthy ecosystem of chipmakers and software creators born to solve application-specific problems,” he said.